By Johan Edman

Because there are always experts who are against almost every change, but we can’t have it like that anymore in Sweden. If there is to be a change, changes must be implemented

(Sweden’s Prime Minister Ulf Kristersson on why the government chose to go against the experts who in a public inquiry (SOU 2021:35) advised against introducing anonymous witnesses, SVT 2022-12-20)

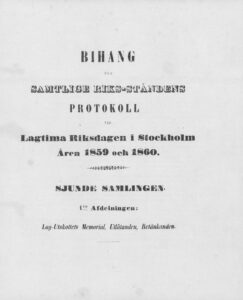

In a criminal policy imbued with populism and resistance to knowledge there is no need for experts or research. It is enough to have a gut feeling, maybe to have heard something or, like Member of Parliament Ola Jönsson, happen to live somewhere where one is supposed to have deeper knowledge about certain crimes: “As I live near the sea coast, I also know that an incredible amount of Danish Scandinavian vodka is smuggled into our country” (Minutes of the Peasant Estate 1859-11-05).

It is however quite a long time ago that Jönsson said this in the Swedish Parliament, as he did it more than160 years ago in November 1859. There was nothing strange about the statement either, and it was neither seen as populist nor resistant to knowledge. As a Member of Parliament in the middle of the 19th century, Jönsson had neither the task nor the opportunity to pursue evidence-based political issues. He was however expected to represent his estate and his local community, and as one of the peasantry’s Members of Parliament from Scania, it was part of the mission to make politics out of things that to the best of his knowledge happened in the Scanian countryside.

The local representation and partisan ambition is still an important part of a Member of Parliament’s mission, even if the four estates (Nobility, Clergy, Burghers, and Peasants) have been replaced by political parties. The forms of political knowledge production have however developed significantly since the 1850s and with this claims that politics should rest to a greater extent on research and unbiased investigations. Contemporary complaints about the development of criminal policy as characterized by politicization, emotional arguments, crime victim focus and populism, a punitive turn and a right-wing shift in criminal policy, is therefore often linked to the fact that it also rests on fragile knowledge. The implicit (and possibly rhetorical) assumption seems to be that the proof is in the pudding – the best criminal policy is based on the best knowledge.

In a new project I will investigate this. The focus of the project is the knowledge base of criminal policy in Sweden over a period of time that extends from the parliamentary discussions preceding the Penal Code of 1864 up until today. I’m interested in whether the knowledge has relied on, for example, independent research, government investigations, newspaper articles, personal knowledge, gut feeling, or something else. Also, what is the development over time, is it possible to identify periods of more research-based, anecdotal, or emotion-driven criminal policy initiatives? How does this development relate to phenomena that are often linked to a knowledge-resistant criminal policy in today’s research, such as the punitive turn, an increased focus on victims of crime and safety, and a more populist and politicized criminal policy?

A historical criminological analysis of this can expose and nuance the development of criminal policy over the past 165 years and contribute to a characterization of this in terms of turns, waves or layers. The current conflict between research-based knowledge and political responsiveness to (or influence of) public legal awareness is not new. As the Swedish Parliament’s Law Committee stated in 1860, every law “should be an expression of the people’s own way of thinking and not only of its jurists” (Law Committee report 1859/60:20). The question of how this has played out in the 162 years between the Law Committee’s disavowal of the experts and our current Prime Minister’s dismissal of criminal policy “experts who are against almost every change” (SVT 2022-12-20) is both an empirically open question and central to the project.

Johan Edman, professor in criminology and associate professor in history at the Department of Criminology at Stockholm University, has mainly conducted research on alcohol and drug policy, the treatment of substance misusers and vagrants, and the knowledge-production at transnational alcohol conferences from the nineteenth century onwards. His last two finished research projects were on the medicalisation of excessive behaviours and the knowledge-base of Swedish alcohol policy during the last century. Currently he is working on a project on the knowledge-base of Swedish criminal policy from the 1860s up until today.